Ever noticed that cursed corner restaurant? The one with a revolving door of hopeful new owners, always promising a fresh concept, then quietly disappearing six months later?

Same building. Same layout. Same fate. You can’t quite explain why...until you realize it’s not about the food, it’s that the environment itself subtly resists success.

I’ve started to feel the same way about a particular kind of AI startup: the “Cursor for X” wave. Cursor for design. Cursor for law. Cursor for filmmaking. Cursor for finance. There are hundreds, maybe thousands, trying to replicate Cursor’s magic: replace a traditional professional workflow with an interface that looks conversational, generative, and assistive.

And to be clear, my aim isn’t to dunk on any of them. Quite the opposite: I want more of them to succeed. But I also think many are struggling for the same reason that restaurant location keeps failing: the environment looks appealing, but hides a missing ingredient.

Let’s take Google’s Flow (Veo 3). A few typed words, and suddenly you're staring at a cinematic scene that would’ve made a 2010 Pixar animator cry. It feels like magic. Not usual “smartphone-in-2007” magic. Not “streaming-music-instantly” magic. I mean time-traveler-from-2022-explodes-upon-entry magic.

Google's Flow.

Douglas Adams once captured our psychological relationship with new technology better than any VC memo:

“I've come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

1. Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that's invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

3. Anything invented after you're thirty-five is against the natural order of things.”

– Douglas Adams

Which partially explains why early adopters flock to these tools, not professionals. When I look at who’s posting Veo films on TikTok and LinkedIn, it’s mostly marketers, tech enthusiasts, brand storytellers, and filmmakers who love film, but never quite broke into the industry. Not the seasoned DP, not the editor who’s spent 10,000 hours in Premiere, not the screenwriter who has opinions about Sorkin’s second act pacing.

Beyond the obvious issue around model training data, traditional professionals resist generative tools not because they’re anti-progress, but because these tools strip away the very thing that makes the work meaningful: the craft. You don’t become a screenwriter because you love generating pages. You become one because you love wrestling with scenes, rewriting, listening to dialogue in your head, obsessing over cadence, silence, tension.

A cynical take would be that we’ve entered the age of “athleisure software”: tools for people who want to look like they're doing the work without actually doing the work. But that’s too shallow. I think these tools could unlock something much better. To quote my friend Anish Acharya of a16z, They could create an embarrassment of riches in fields that were previously gated, intimidating, or geographically clustered, just like WordPress, Ghost, and Substack did for writing.

But first, we need to acknowledge the real gap:

The tools democratize production. They do not democratize expertise.

It’s not enough to give an amateur filmmaker access to a generative Hollywood engine. If it were, every kid with a Leica would have become Yousuf Karsh. Tools don’t transfer taste. They don’t encode judgment. They don’t whisper why something works.

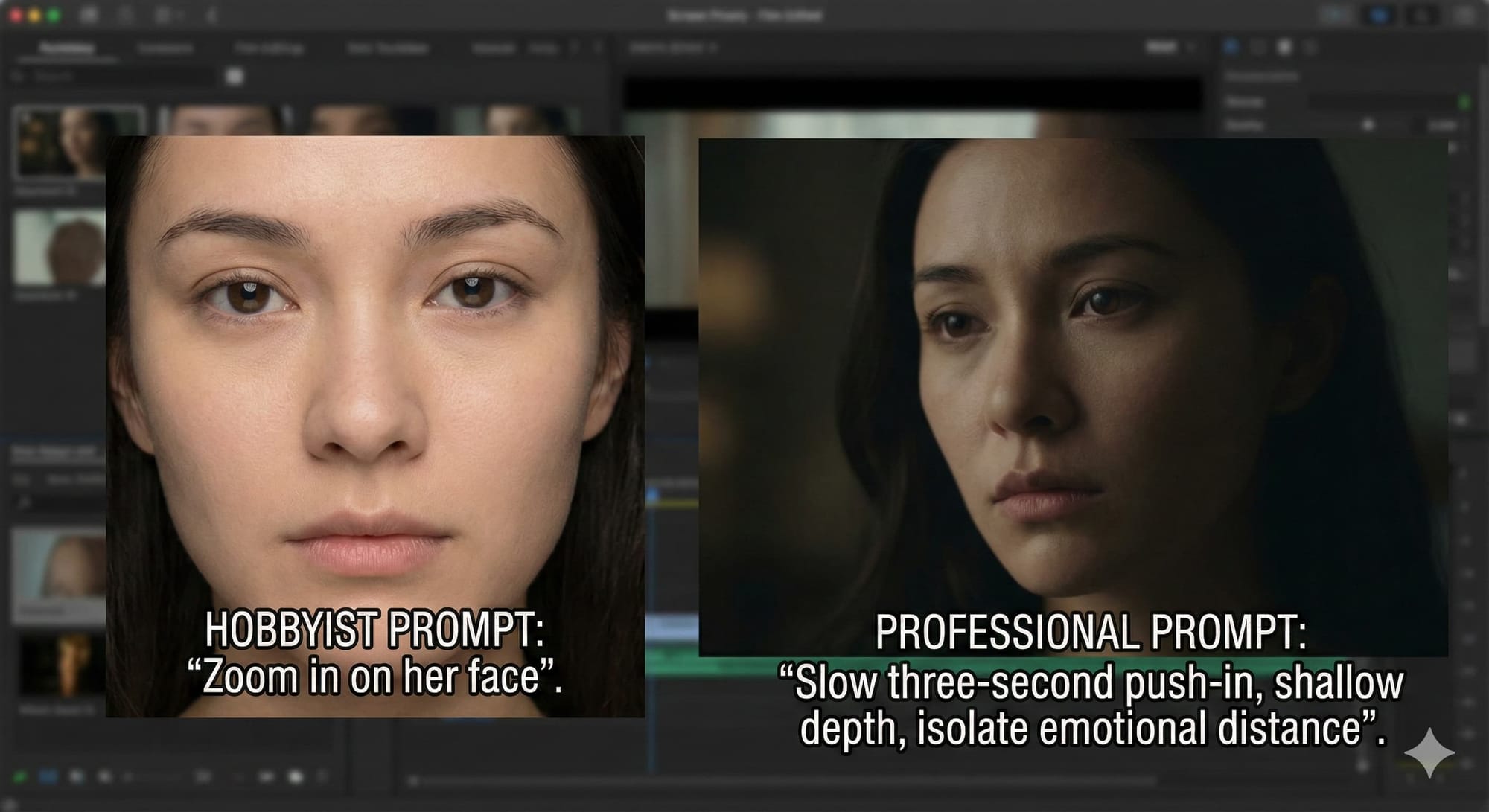

Whereas hobbyists try to intuitively replicate the films they love, aspiring professionals deeply study the medium. They watch movies as if they’re reverse-engineering them. They read screenplays not for plot, but structure. They freeze frames to analyze lighting, pacing, framing, emotional pressure. They learn the grammar of film.

Hollywood has a language that AI models increasingly understand, but hobbyists don’t.

A novice says:

“Give me a dramatic close-up.”

A professional says:

“Give me a slow, three-second push-in for emotional isolation. Depth at f/2.0. Let the background collapse.”

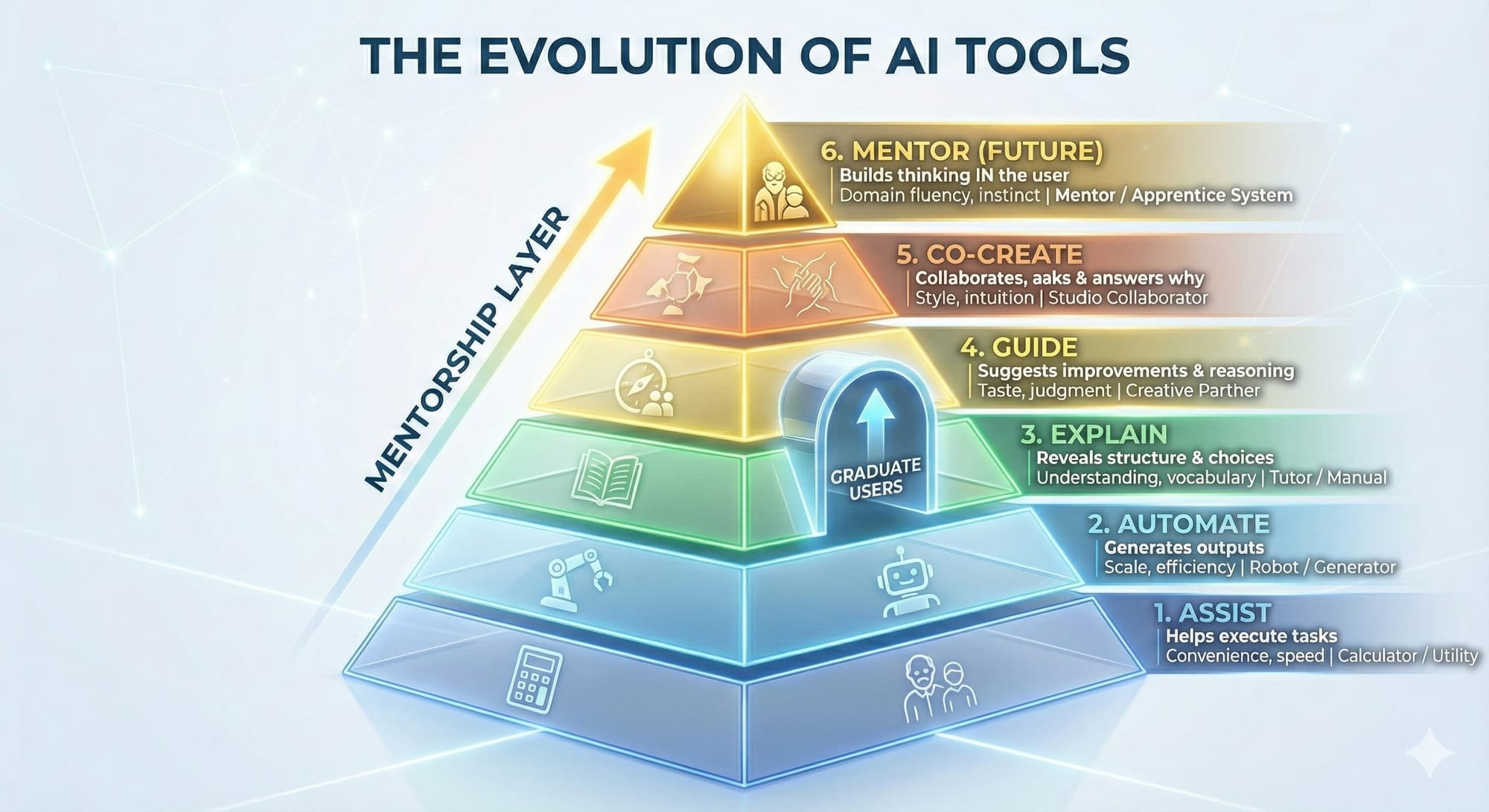

That’s the point: right now, Cursor-for-X tools help people produce, but not understand. They empower hobbyists, but they don’t graduate them. They generate, but they don’t guide.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Some of the most transformative software in history teaches people how to think like professionals. GarageBand reveals structure and harmony by letting you feel how tempo, layering, and progression shape emotion. Procreate teaches lighting, texture, and composition through feedback your eyes can’t ignore. Webflow exposes hierarchy, spacing, and spatial rhythm until you start thinking in systems, not pages. And over time, you stop just making things, you start making choices.

Software is weirdly good at this kind of teaching. It doesn't judge. It doesn't sigh. It doesn't say “you should know this by now.” It can nudge. It can show patterns. It can expose structure and vocabulary without shaming you. It’s the closest we’ve ever come to a judgment-free apprenticeship.

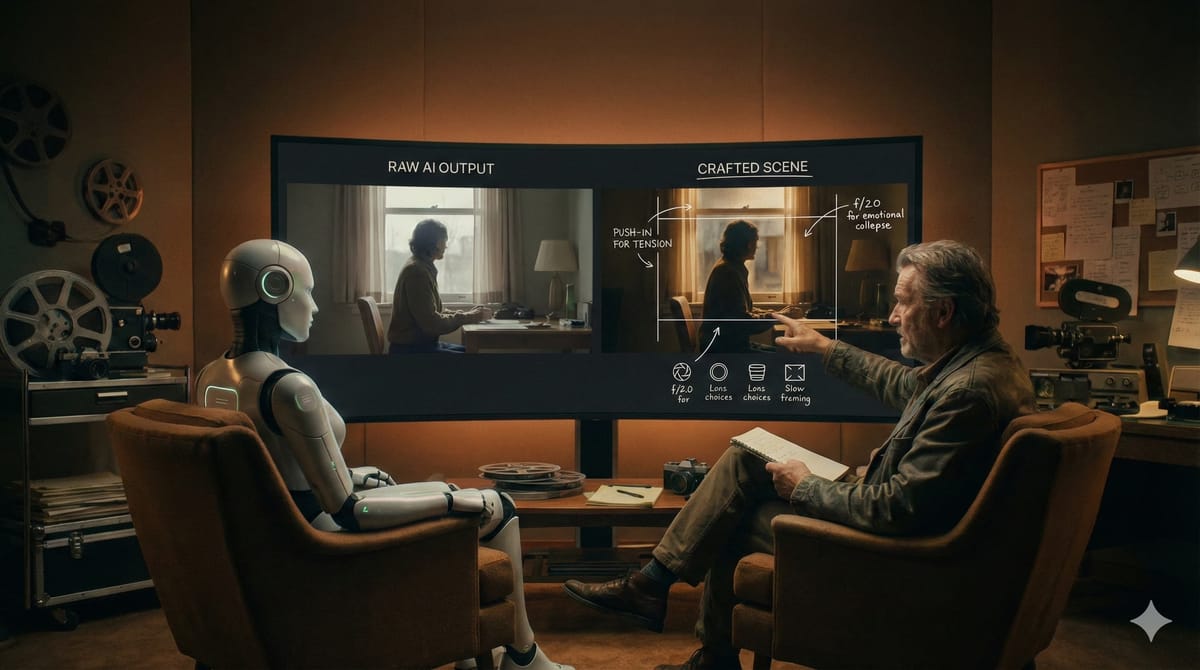

The tools that succeed in this space won’t be the ones that generate the prettiest output. They’ll be the ones that help users develop judgment: that whisper, suggest, question, and reveal.

Tools that don’t replace professionals, but help create them.

And when that happens, we’ll stop calling them “Cursor for X.”

Not because they failed, but because the metaphor was too small.

They won't feel like assistants.

They’ll feel like collaborators.

They’ll feel, strangely, like mentors.

Onwards.

Member discussion